If you want to know how resilient Filipinos are, take the first flight out to Tacloban City in Leyte, an hour from Manila. By this time, everyone–Filipino and foreigner alike–knows the city by name. It is impossible to forget what happened to this place two years ago, during the strongest typhoon in history to ever make landfall.

In November 2013, I was one of those who watched in horror, from the comfort of my living room in Metro Manila, as 300 kph winds and a seven-meter storm surge nearly decimated that historic city in Eastern Visayas. A few days later, as the winds blew another way, images of Tacloban revealed nothing but bloated bodies, ravaged houses, crying children, lost parents—the remnants of once happy lives—scattered on the streets.

Imagine what I was thinking when a book project required me to travel to Tacloban, 16 months from that tragic day.

“Do you think there are ghosts there?” I asked a friend, who knew that I feared only three things in life: big spiders, flying cockroaches and ghosts (okay, and occasionally, ugly frogs). She just laughed. I took that as a yes.

I scoured Tripadvisor and every other booking website for the happiest-looking place to stay in Tacloban. I did not want to sleep in old hotels; I was traveling solo so I had no plans of being alone in musty rooms that could stir my imagination. My mind was still filled with images of the dead and dying.

When I chanced online upon a new hostel called Yellow Doors, with its doors and windows painted—of course—a bright, sunshiny yellow, and its dorm beds divided by curtains with attitude, I booked it right away. I got one of only two private rooms, trusting all six raving reviews it had then (it’s now the top bed-and-breakfast on Tripadvisor).

On the way to the hostel from Tacloban airport, I noticed a lot of construction sites. The same road, which in 2013 was lined with unidentified bodies in black bags, were clear; houses were newly painted and businesses went on as usual. It was an entirely different picture from the one in my mind.

At the Yellow Doors reception, the first thing that caught my eye were the words painted on the wall: “We are made of stories.” A wall after my own heart, I thought.

The receptionist, a lovely lady, led me into the room and told me to have coffee and a toast. Stories + coffee = I am home.

For four days, I used Tacloban as a base from which to explore the southern parts of Leyte and a remote town in Samar, checking on communities that received shelter assistance from international aid organizations and the government. It was humbling to see the strength of people who have lost everything but hope. They, with their ragged faces and wrinkled hands, convinced me that there was nothing in this life that a faith-filled spirit could not overcome.

In fact, in Tacloban, people did not only overcome; they began to fashion a whole new life from the scraps of their awful experiences from Haiyan.

Yellow Doors, for instance, was literally built from junk that its owners, siblings Jake and Trixie Palami, gathered in the aftermath of the super typhoon. “There were a lot of things on the street, so we just picked them up,” Jake recounted as he struck up conversation at the hostel’s receiving area where I was working, thanks to free WiFi, one afternoon.

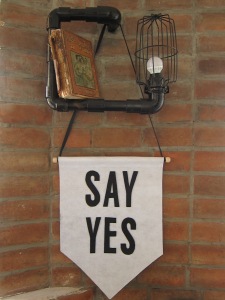

Because Trixie was an interior designer, it did not take long for them to repurpose the scraps into beautiful furniture, Jake said. Doors were used as walls and tables; chairs were patched; pipes became lamps; old wires were twisted into an artsy “YD.”

Jake and Trixie decided to put up the hostel due to the demand for decent, affordable accommodations for aid workers that descended on Tacloban post-Haiyan. The siblings found a dilapidated building on Burgos corner Juan Luna streets, renovated it, and ended up with a charming B n’ B that’s now a favorite among visitors to the city.

A few blocks away, several other hostels have sprouted. Another charmer, Lorenzo’s Way is owned by the same people that run Leyte Park Hotel, albeit this four-bedroom affair is cozier and cheaper. It serves fantastic breakfast, too.

All over, old restaurants were rebuilt and new cafes opened.

Ocho, one of the local favorites, was one of the first restaurants to re-open in the wake of Haiyan, serving a few of its signature dishes that have become comfort food. Pop-up bars and kitchens are popular among young troopers.

Surprice on Burgos Street is a great place to fill up after a long day; Chew Love offers cuteness overload, plus a surprisingly cheap banana split; Libro Atbp. on Sto. Nino Street is a default destination for bookworms and coffee-lovers; Jose Karlos Café across the Sto. Nino Church, would give Starbucks a run for its money with all the trappings of an ancestral home-turned-coffeeshop.

On my first night, I knew four days would not be enough to eat my way through Tacloban, however small the city was. Friends of my sister and people I’d interviewed would take me to  different places every night. Sometimes I would end up having three dinners and two lunches. Food drowned all thoughts of ghosts, and I would sleep with a happy tummy.

different places every night. Sometimes I would end up having three dinners and two lunches. Food drowned all thoughts of ghosts, and I would sleep with a happy tummy.

In the morning, the whir of construction machines and noisy drilling would wake me up. But that was fine. It meant something good in a place like Tacloban.

It signaled a new day.

It’s been two years since the world stood still, shocked to its core, and wept like never before. Tacloban, the Haiyan forsaken city, will remember once again in this history-worthy day the worries, troubles, challenges, agony, havoc, and pain that the typhoon gave when it left its mark on everyone’s lives. The incident resulted for Tacloban to be catapulted to the world stage and be lamented by almost everyone in every nation of the world. But, also, this was the day when faith, courage, resilience, fortitude, and the “bayanihan” of the masses served as the key to survival and renewal.

Hoooooray Tacloban 🙂